Scarred by bare metal programming during my formative years, I consider the speedup from multithreading worth pursuing no matter how limited a form of it you’ll get, and no matter how hideous the hacks you’ll need to make it work. In today’s quest, we shall discover the various ways in which threads don’t work in a Python, Wasm, and especially a Python on Wasm environment, and then do something about it — even when that something could get us shunned from polite society. In the end, we’ll arrive at a working setup for limited yet performant multithreading, usable for soft real time programs caring about sub-millisecond overheads which we’ll attempt to minimize or eliminate (GitHub links: Python running C threads on Wasm; a simple C++ thread pool for Wasm.)

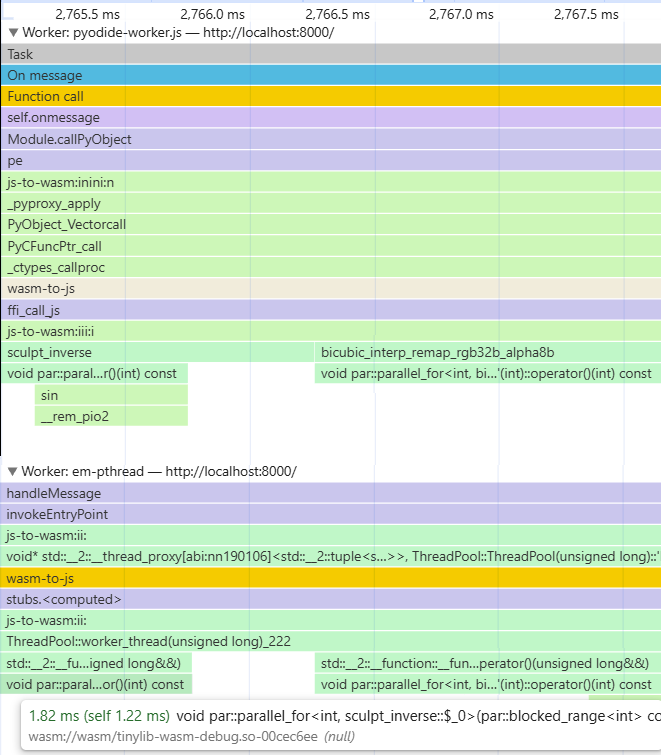

What this does is shown in the screenshot below1 — a browser thread running Python and calling a C function sending work to a pool of C threads, one of which (“em-pthread”) is shown at the bottom.

I knew nothing about WebAssembly, and very little about JS and the rest of it, when I got into this. I am still shocked by what I’ve discovered. The world’s most successful secure VM for running untrusted code turns out to be a complete hack wrapped in a shortcut inside a workaround2 — though I must admit that I kinda like it that way?!.. This is not to say that I really learned the platform — please correct me when I’m wrong, and please provide me emotional support when I’m right, as I’m muttering things like “so pthread_create fails because someone put API.tests=Tests into some JS file?!..” or “so the wrong C function gets called because dynamic linking is quietly working incorrectly?!..”

Plain pre-no-GIL Python

At first glance, there’s nothing to talk about here — everybody knows that Python is about to lose the global interpreter lock, but that work isn’t finished yet, so right now you won’t get a speedup from threading, unless your threads wait on I/O a lot. That a C library used from Python can spawn its own threads to mitigate this problem is not news, either.

However, a couple of things below are appreciated less widely. I bring these things to your attention lest you discover them on your own, and repeat my mistake of actually trying to use them. Incidentally, not using these things will turn out to be particularly beneficial on WebAssembly.

The first thing is that the GIL is released when a function is called via ctypes3. So maybe we could write serial C functions and call them from Python worker threads? Well, it’s fine for work taking tens of milliseconds, but for very short tasks, the overhead of Python thread pool management is significant.

The second thing is that ctypes can pass a Python callback to a C function. This is expected of a C FFI package, but ctypes generates machine code at runtime to make it work, which is impressive4. Anyway, seems like we could export a C parallel_for function to Python, and run Python callbacks in a C thread pool?

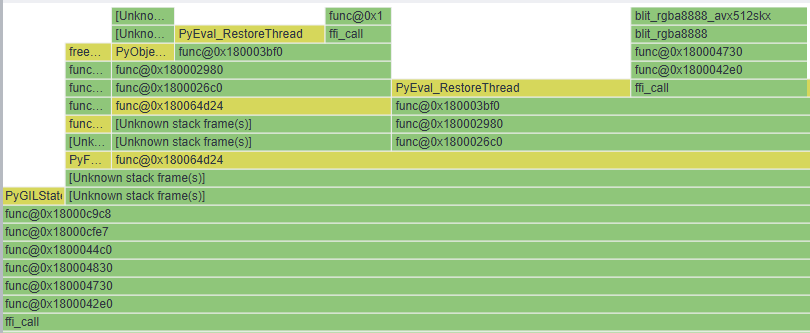

This is fine for letting Python code use C threads, to avoid a second pool of Python threads. But even the thinnest Python callback that calls back into C adds overhead too large for short tasks. You can (sorta) see this if you zoom into this VTune screenshot, with the first three quarters of the timeline occupied by Python runtime functions — BTW, mostly functions seemingly unrelated to the GIL:

The upshot is that for speeding up a sequence of relatively short tasks (like real time input handling), the way to go is a serial Python flow calling C functions sending tasks to C worker threads, with zero Python code running in the workers.

It turns out that on top of its performance advantage, this style has the added benefit of being the easiest to port to WebAssembly by far. In fact, despite getting no threading whatsoever under Pyodide, the Python Wasm runtime, out of the box, you might think that this style would “just work” — since we’re not using Python threads, right? We’re just loading a C library which uses threads, and C threads work on Wasm, right?

Wrong. “The easiest way” doesn’t mean easy — you do not just load a C library using threads on Wasm.

Life inside an array

Wasm started out, in the days of asm.js, as a way to compile C to a subset of JavaScript that a JS engine can optimize well, by emitting code like (x|0) which persuades JS engines to treat x as an integer, rather than something with a statically unknowable type. Later, a proper intermediate instruction set representation was designed for the compiler to emit, so the x|0 craziness went away.

However, it’s still a C program running inside a JavaScript environment. How does this even work? Well, the program’s data is stored inside a JavaScript array5. When malloc runs out of space in this array, it calls the JavaScript function Memory.grow to enlarge the array, the way it would call sbrk on Linux. (In general, the JS runtime is the OS of the Wasm program — its way to interact with the world outside the JS array is to call an “imported” function implemented in JavaScript6.) C pointers are compiled to indexes into this array. To access a C array from JS, you actually use JS array views with names like HEAPU8 (for uint8 data), indexing into entries starting from the integer value of the C array base pointer.

So how does Python run in a JS environment? Well, CPython is a C program which was compiled to run inside a JavaScript array, and ported to use the “OS” (actually, JS) APIs available on the web and/or Node.js. Pyodide is that port — a very impressive feat.

So, we’ll build our shared library for Wasm (where programs are called “main modules” and dynamic libraries are called “side modules” — odd names underscoring the fact that you can have several main modules within one OS process, each running inside its own JS array.) And we’ll load our side module from Pyodide using ctypes.CDLL as we would anywhere else, and it will happily spawn threads.

Except it won’t load; it will complain that you’re trying to run it inside the wrong kind of JS array. You see, there’s ArrayBuffer, an array which you can’t share between threads, and there’s SharedArrayBuffer, which you can. (“I’m afraid I can’t do that” due to a mix of security considerations and historical baggage is a recurring theme on the web platform.) Since your side module was built with -pthread, it needs to run inside a SharedArrayBuffer, but Pyodide was built to run inside a plain ArrayBuffer.

My first thought was, “big deal — I’ll give Pyodide, this compiled blob of Wasm, a SharedArrayBuffer instead of an ArrayBuffer to run in” — it’s not like it “feels” what it’s running inside, right? It’s the same load/store instructions in the end?

Well, yes, but. Long story short, you must build Pyodide from source with -pthread to load your side module. There are many reasons for this, such as side modules getting the pthread runtime from the main module, and needing emscripten-generated JS for this runtime to work (did I mention that emscripten produces a giant .js output file alongside the .wasm file — about 60K LOC for Pyodide?)

Luckily, Pyodide provides a Docker container for the build, and $EXTRA_C/LDFLAGS env vars that you can set to -pthread; it’s rather nice. To then build your side module, use emscripten from the emsdk/ directory produced by the Pyodide build process, or things will silently fail7.

You will also need to serve your web page with a couple of HTTP headers (Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy same-origin, and Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy require-corp8) — absent which the browser will refuse to give you a SharedArrayBuffer (I’m afraid I can’t do that.)

And you might want to build Pyodide to use mimalloc instead of dlmalloc to avoid a global lock in malloc/free, though I’m not currently doing it. Mimalloc uses more space, and even with dlmalloc I’m seeing tabs with Pyodide where Python’s tracemalloc reports tens of megs, but the Chrome tab tooltip reports hundreds of megs9. A more efficient if less pleasant approach is to avoid malloc in parallelized code.

While we’re at it, it’s notable that dynamic allocation of large chunks is space-inefficient when “living inside an array” without mmap. And funnily enough, this is exactly how things work on the bare metal — if you allocate and free lots of large & small chunks, you’ll get heap fragmentation to the point of running out of memory, so you learn to malloc the larger chunks up front.

(This doesn’t happen on fancier systems with virtual memory, where malloc mmaps large chunks instead of carving them out of the one big array grown & shrunk by sbrk. Then free calls munmap, and since a contiguous virtual address range can be backed by non-contiguous physical pages, you can always reuse the pages for another large chunk later — you don’t suffer from fragmentation. By forcing malloc to look for large contiguous slices inside a SharedBufferArray, the bleeding edge web VM is sending us to knuckle-walk down the road traveled by embedded computing troglodytes.)

Fragile – handle with care

Up until now, nothing really gross — so you need to rebuild from source and use a specific compiler version, big deal. On the other hand, up until now, we didn’t actually spawn any threads, either. Our side module will now load just fine — but it will promptly get stuck once it spawns a thread and tries to join it.

One splendid thing on the web is how “you can’t block the main thread” — “I’m afraid I can’t do that.” Of course you can block the main thread by doing some slow work in JS, but you’re not allowed to block by waiting (you should instead yield to the event loop — all that async business.) Therefore, using pthread APIs from the main thread tends to be a bad idea. You can actually get emscripten to busy-wait in the main thread, instead of the disallowed proper waiting. But the workers talk to the main thread to access many kinds of global state, so waiting might deadlock.

So the first order of business is to move your code using Pyodide to a web worker10. Having done that, you might observe that you’re stuck at the same point, because of the following:

When pthread_create() is called, if we need to create a new Web Worker, then that requires returning to the main event loop. That is, you cannot call pthread_create and then keep running code synchronously that expects the worker to start running - it will only run after you return to the event loop. This is a violation of POSIX behavior and will break common code…

So we yield to the event loop — yet we still remain stuck. That’s because the emscripten-produced JS runtime code making threads kinda sorta work is:

- broken by Pyodide customizations; but also

- missing Pyodide customizations that any module would need to support threads; and finally is

- broken, period, (nearly) regardless of Pyodide.

Here are the specific problems and their workarounds, in increasing order of ugliness.

As a warmup, you’ll find that you run the wrong JS code when spawning your C thread. In a JS environment, the so-called pthread runs in a JS “web worker” thread, the entry point of which is a JS file it gets in its constructor and runs from top to bottom. Your C thread entry point is eventually called from that JS file. Emscripten produces a single JS file, pyodide.asm.js in our case, which wraps the module both in the main thread and in the workers. So to implement pthread_create, the file pyodide.asm.js needs to initialize a JS worker with itself. However, like any JS file, pyodide.asm.js doesn’t know its own URL. Its attempt to find out instead produces the name of your Pyodide-using worker’s JS file, and hilarity ensues.

Now if Pyodide was designed to support threads, its loadPyodide function, which wraps the emscripten-generated wrapper pyodide.asm.js, would probably accept the file URL as a parameter — and pass it to pyodide.asm.js in the "mainScriptUrlOrBlob" key that the generated code seems to expect. Since my workarounds are too incomplete to upstream to Pyodide anyway, I didn’t bother to fix this properly, and passed the name thru some global variable.

A more curious class of issues you’ll discover is code (smack in the middle of pyodide.asm.js’s 60K LOC) doing things like API.tests=Tests, and failing when running in the pthread worker. Grepping will reveal that the offending code comes from Pyodide, rather than being generated by emscripten. How does it get into pyodide.asm.js? Not sure, but I think a part of the thorny path is, the .js files get concatenated by make, then grabbed by a C file using the new #embed preprocessor directive, and then pulled out from the object file into pyodide.asm.js by emscripten. In any case, you just need to strategically surround the offending bits with if(!ENVIRONMENT_IS_PTHREAD) — that’s a global variable set in the generated code by checking if the thread’s name is em-pthread (the check is done differently on the web and under Node, of course.) And with enough of those ifs, you’re past this hurdle.

This is starting to stink, but you’ve probably smelled things worse than this. This is definitely the first case I’ve ever seen of a threading implementation fragile enough to require effort from higher-level code (in this case Pyodide) both to support it and to avoid breaking it. But zooming out a bit, most of us have seen worse examples of difficulties making code do things it wasn’t meant to.

No, the real horror hides behind this succinct assertion in the Pyodide docs:

“The interaction between pthreads and dynamic linking is slow and buggy, more work upstream would be required to support them together.”11

We’re about to discover what this means.

How “threads” do “dynamic linking”

I sort of dismissed the stark warning in the docs because of the optimistic comment from 2022 from an emscripten maintainer (on the issue “Add support for simultaneously using dynamic linking + pthreads”, from 2015):

I think this is largely complete. We still warn about it being experimental, but it should work % bugs. We can open specific bugs if/when they are found.

Another reason I wasn’t worried were my limited ambitions. I don’t dlopen from threads or whatever — I just spawn a pool of threads from a side module, how can it not work? Of course this question reveals a lack of imagination — the real reason I wasn’t worried. Like, what do threads even have to do with dynamic linking? Thread-local storage, which does get awfully ugly in the presence of dynamic linking? Well, I don’t use TLS. What could go wrong?

This thinking is sensible with real threads doing real dynamic linking. The basic part of mapping new code and data into the process address space is sort of orthogonal to threading — all threads “see” the new code and data simply because they share the address space.

What about Wasm threads — don’t they share address space, too, that SharedArrayBuffer? Well, that’s for data, not code. Remember how C data pointers become indexes into the SharedArrayBuffer? Well, function pointers become indexes into wasmTable, a different array. Here, each index corresponds to a whole function, not an instruction. This is nice in that you can’t jump into the middle of a function (“I’m afraid I can’t do that”) — a part of Wasm’s control flow integrity features (of course data integrity inside the [Shared]ArrayBuffer is no better than in C — but the considerable extent of CFI is still a good thing.)

What you’ll find out when your thread finally runs, and the wrong function is called instead of your entry point, is that wasmTable is private to each thread. Which means that Wasm “threads” are more like processes with data in shared memory. The code can be completely out of sync — as in, thread A has function f at index 47, and thread B has f at 46.

Of course, the emscripten runtime — the C and JS code working together — makes an effort to keep the tables in sync. When a pthread starts, it gets a list of dynamic libraries to load in the same order its parent did. And when a pthread runs and dlopens a library, it “publishes” this fact thru a shared queue, and waits for the other threads to notice and dlopen the library, too. It’s impressive how hard Emscripten tries to make dlopen and pthreads work despite the offbeat sharing model — though notably, this is another potential source of Wasm-specific threading deadlocks:

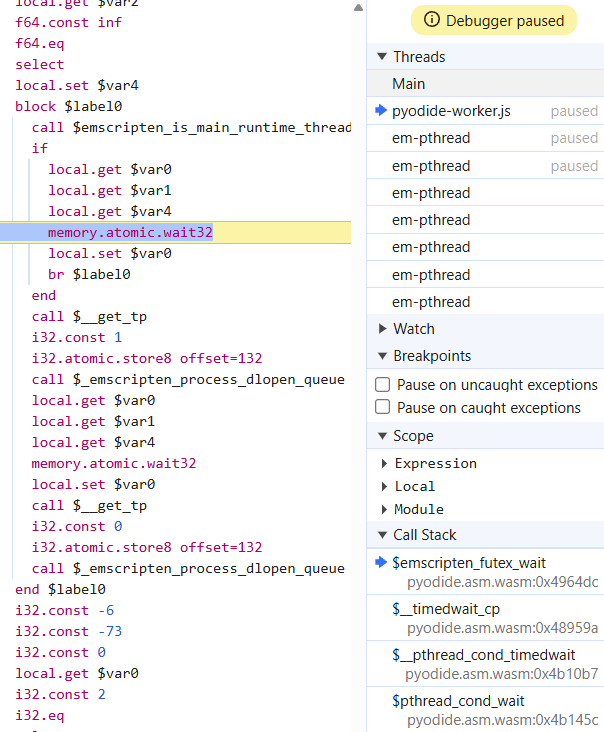

In order to make this synchronization as seamless as possible, we hook into the low level primitives of emscripten_futex_wait and emscripten_yield. … If your applications busy waits, or directly uses the atomic.waitXX instructions (or the clang __builtin_wasm_memory_atomic_waitXX builtins) you maybe need to switch it to use emscripten_futex_wait or order avoid deadlocks. If you don’t use emscripten_futex_wait while you block, you could potentially block other threads that are calling dlopen and/or dlsym.

In particular, you will deadlock not only if you wait for a child to start without yielding to the event loop, but also if you dlopen before yielding and letting the child start — so don’t. But to go back to our nastier problem — with all this runtime work, how does a child thread get f at index 46, when the parent has it at 47? Ah, that’s because code can add entries to wasmTable — and you don’t have to be “the dynamic loader,” some JS runtime code, to do it! It can just as well be some other JS runtime code! I think that there’s something Pyodide-specific doing this, but not sure; you might pass a dynamically created callback as a function pointer that way, for instance.

In any case, for init-time dynamic linking, the current JS runtime simply has the parent send a list of modules to load, and the child loads them in that order. This doesn’t account for the stuff put in between modules in the parent. My workaround is to modify the emscripten-generated JS code to keep the offsets to which modules were loaded in the parent (that’s simply wasmTable.length at the time when loading happened.) I then send them to the child, which grows the table to recreate the parent’s gaps between the modules. (I don’t care what’s in these gaps, on the theory that C code not interacting with Python code won’t need it.)

I did not patch the runtime enough to handle the case where a pthread returns, and the JS worker is then reused for another pthread; you will probably get exceptions in the dynamic loading code in the new pthread. I also didn’t bother with offsets of stuff dlopen’d later at runtime. I think that the mismatch between the Unix process model and the Web-workers-with-a-SharedArrayBuffer model is quite large, and my chances to bridge it are smaller than the chances of the actual emscripten team, and they probably gave up on fully bridging it for a reason. In fact, there’s a shared-everything-threads proposal which aims to share wasmTable, among other things, to make dynamic linking not as “slow and buggy” as the Pyodide docs mentioned in passing, and as we’ve now learned thru bitter experience.

Another reason I didn’t bother fixing issues outside my use case is that even said use case, that of a pool of pthreads which never exit or dlopen, and all they do is run parallel_for’s, doesn’t actually work with off-the-shelf code, as we’ll immediately see. We’re clearly not enabling threads here — we’re “enabling” “threads”, meaning, we’re trying to use platform features which don’t add up to “real” threads by design. Best to focus on a narrow use case and make sure it actually works.

A small, warm pool

With these workarounds12, we can compile an off-the-shelf framework like TaskFlow, and run a parallel_for example. Once we work around needing to yield to the event loop before the thread pool becomes usable, it turns out that TaskFlow occasionally gets stuck in a parallel_for — all threads are stuck waiting:

I have no idea why, and whether it’s a “real” Wasm compatibility issue in TaskFlow, or evidence of my attempt at enabling threads in Pyodide being incomplete (as we’ve seen, on Wasm, threading is easily broken by the code you integrate threading into.) I decided that my adventure debugging hairy code I know nothing about stops here — my needs are much more modest than TaskFlow’s feature set, so I am just rolling my own thread pool.

I only do parallel_fors, with nested or concurrently submitted parallel_fors serialized. To avoid things that “are supposed to work” in C++ but turn out to be broken or non-trivial to enable on Wasm, I’m only using synchronization primitives compiling straightforwardly to Wasm builtins. Those builtins are:

- The usual atomic memory operations (load/store, read-modify-write, compare-and-swap, fence.) These are Wasm instructions compiled to native CPU instructions or short instruction sequences; it’s hard to imagine how the Wasm “JS OS” business can break any of these. It’s also hard to imagine how a C++ implementation of std::atomic<T> can mess things up, so I just use std::atomic rather than emscripten builtins.

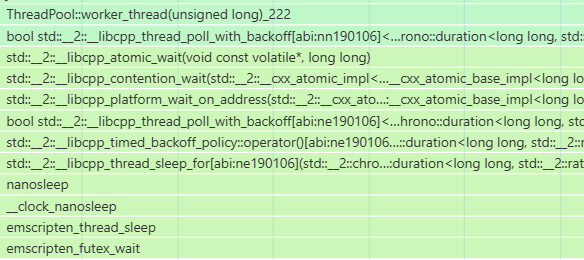

- The OS-assisted notify/wait — these map to futexes (or their equivalent on not-Linux.) How much hides behind the word “map” here at the Wasm VM side I don’t know. I do know that the C++ standard library std::atomic<T>::notify/wait methods do quite a bit on top of the builtins (check out the screenful of C++ garbage below) — so I use emscripten_futex_wake/wait instead13; you can switch to the std versions by commenting out a #define.

In case futex performance is an issue — it certainly is in my tests, but YMMV — I also have a “warm pool” feature where the threads busy-wait for work instead of waiting on a futex. (This warm pool business is one reason to roll my own pool — off-the-shelf load balancers don’t have this, though some of them busy-wait a little bit before waiting on a mutex, which is similar.)

Of course, such busy-waiting makes fans spin and drains batteries14. An example of mitigating this is, you only keep your pool warm between your pointer-down and pointer-up event, or you could go further and only “warm” the pool once you start dropping pointer-move events. A “cool” pool waits on a futex, which is pretty low-overhead — but the overhead could count with many short parallel_fors submitted quickly enough after each other.

A final wrinkle is that parallel_fors are serialized until all threads are ready to execute work. This avoids an init-time slowdown where someone uses a parallel_for and ends up waiting for hundreds of ms for Wasm threads to start — or deadlocks because they won’t start without yielding to the event loop15. In production, it’s also a better fallback upon some environment issue where the threads failed to run, period — compared to getting stuck forever waiting for them.

This warm, limited, but fast, small, and seemingly robust pool is available on GitHub. It’s more “works on my machine” than “battle-tested” at the moment, but you could “come to trust it through understanding” more easily than most such code, it passed some TSan testing (which found a bug), it’s portable, and it works in the browser, which apparently isn’t trivial for a load balancer16.

Conclusion

A Pyodide fork you can build with the “threading support” described above is available here.

We shall conclude with a brief attempt to defend both our ends and our means against the accusation of unacceptable barbarism — an accusation which I acknowledge to be quite understandable. I mean, the above should be enough to get why Pyodide doesn’t ship with threading support — Python dlopens a lot, and Pyodide is supposed to work out of the box for a large number of Python users, who will just give up on this Python in the browser business if things break in ways described above. Shouldn’t we avoid half-baked hacks, and produce solid code built on a solid basis?

My reply to this is that features matter, performance is a feature, a hack is fine if you know what you’re doing, and a lot of good stuff comes about through a series of hacks:

- By “features matter,” I mean that between an ugly implementation of something and no implementation at all, ugly is better. “Let’s do it properly” instead of a quick hack I can get behind. But “let’s not do it at all” is going overboard — getting things done is kind of the point, and you don’t give up on doing stuff out of a sense of aesthetics.

- By “performance is a feature,” I mean that, say, threading makes things several times faster, and this can be the difference between a feature that works fine, and one that is unusable.

- The trouble with a hack is how often it breaks and what happens when it does. A hack is fine if it’s unlikely to break, or if it tends to break “loudly” during testing, rather than breaking quietly in production, etc. A lot of the risk can be mitigated by aiming low — if your system is simple and doesn’t count on too much, not much will break, and you can figure it out when it does. A simple system has an easier time leveraging ugly hacks to get tangible benefits.

- The WebAssembly platform is quite hacky, and this is still visible in 2025; looks like it was worse earlier on. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Wasm is becoming the most successful VM for running untrusted code in a wide variety of languages. The way it’s made is not only hacky but makes it easy to further hack on, which means you can integrate it into some odd environment with very reasonable effort. For an example of a massive hack, look at the “asyncify” feature where normal C++ code is made to yield to the event loop by emscripten. This implementation style is what helped C spread in the first place — and the opposite of what I think somewhat limits the JVM, which is a serious thing you can’t just add a bunch of hacks to in order to adapt it to something.

I can’t say that I love ugly, hacky code — I’ve met bigger fans of “pornographic programming”, as McCarthy called it. But ugly and hacky is much better than solid, well-designed, and too rigid to work around the limitations of. For what it’s worth given my very little experience, I hereby recommend WebAssembly as fairly hackable.

See also

“This one is admittedly a hack, and a dirty one,” says a Wasm-related writeup about one of its sed invocations modifying Emscripten-generated JS. I’m linking to it primarily as an attempt to present my methods of dealing with this stuff as completely normal.

P.S.

“Printf debugging” JS17 was harder than usual. Apparently, console.log is aggressively buffered, and if your threads print in some short test on Node, you might never see the prints. On Node, fs.appendFileSync helps, and you can install a process.on('uncaughtException') hook doing this. In the browser, pausing in the debugger seems to flush console.log prints.

Thanks to Dan Luu for reviewing a draft of this post.