If you aren’t deeply frightened about all the issues raised by concurrency, you aren’t thinking about it hard enough.

This post introduces checkedthreads – a free framework for parallelizing C and C++ code, and for automatically finding every race condition that could potentially manifest on given program inputs. It comes with:

- a Valgrind-based checker for thorough verification

- an event-reordering scheduler for fast verification

The code in checkedthreads is fresh and wasn't used in production yet. However, tools using the same approach have been successfully used for years in automotive safety software containing millions of lines of code written by many dozens of developers.

A nice use case for checkedthreads is, you have a complex, serial program that you want to parallelize. With checkedthreads, you'll be able to run your test suite and be sure that you have no parallelism bugs – as sure as you'd be about, say, memory leaks. And if your parallelization does introduce bugs, the Valgrind checker will pinpoint them for you, so that you can quickly fix them.

In what follows, I explain how race detection works in checkedthreads, and then briefly discuss its other features and how to get started with it.

***

Why are threads so error-prone? We're accustomed to see the root of the problem in mutable shared memory. Commonly proposed alternatives to threads avoid mutable shared memory. For example, pure functional code gets rid of the "mutable" part, and process-based parallelism gets rid of the "shared" part".

While processes and pure FP have their virtues, I believe that mutable shared memory is not, by itself, what makes threads bug-prone. You can keep mutable shared memory and eliminate the bugs. Moreover, as we'll see, it's perfectly possible to eliminate shared memory – and keep the bugs.

What, then, is the root of the problem? I believe what we need is to find the right interfaces. Threads and locks are great low-level primitives, but a bad interface to use directly in source code.

In this sense, threads are not unlike goto. Goto is a horrible interface for human programmers. But it's fine as a machine instruction underlying higher-level interfaces ranging from loops and function calls to exceptions and coroutines.

What higher-level interfaces do we have on top of threads? One such interface is fork/join parallelism – parallel loops and function calls. ("Loops and function calls" is notably very similar to the most popular interface on top of goto.) "Fork/join", because starting a parallel loop logically forks a thread per iteration, and those threads are joined back when the loop ends:

Examples of fork/join interfaces include TBB's/PPL's ****parallel_for**** and parallel_invoke, and OpenMP's #pragma omp parallel for. Checkedthreads provides something similar as well:

ctx_for(_objs.size(), [&](int i) {

process(_objs[i]); //in parallel for all i's

});

Fork/join parallelism is well-known, and appreciated for its automation of synchronization and load balancing. But how does a fork/join interface help with program correctness compared to raw threads and locks?

We'll see how fork/join helps by looking at two methods to verify parallel code – event reordering and memory access monitoring. Both methods are implemented by checkedthreads and together, they guarantee near-100% freedom from parallelism bugs.

We'll discuss why these methods are so effective with fork/join code – and why they are comparatively ineffective with raw threads.

Since parallel function calls can be implemented using parallel loops, we'll only explicitly mention parallel loops. And we'll only discuss "pure" fork/join programs – programs where forking and joining is the only synchronization mechanism.

That is, code inside a parallel loop can access stuff written by whoever spawned the loop – and code after the loop can access stuff written in the loop. But you can't access shared data using semaphores, atomic counters, lock-free containers, etc. – such accesses will be flagged as bugs. To synchronize threads, you must fork or join.

Lastly, we'll assume that you can't proceed until the loop you spawned completes – and you can't wait for anything but a loop you spawned yourself. (This is an obvious property of code spelled using some kind of a "parallel for", but not of other fork/join interfaces; a recent paper calls this property "strict fork/join parallelism".)

We're thus assuming both "purity" and "strictness"... which sounds more restrictive than it is – but that is a separate topic. And now, with all the assumptions spelled out:

Why fork/join code is verifiable – and why raw threads aren't

First, let's consider event reordering – a cheap and effective verification method.

Suppose thread A writes to address X, and thread B concurrently reads from X. Then B might see A's write or it might not, depending on timing, so it's a bug. A cheap way to find this bug is, don't run the program with the production thread scheduler, where the order of events depends on timing.

Instead, use a debugging scheduler which purposefully and deterministically reorders events. Make it schedule things so that in one run, A's write precedes B's read – and in another run, B's read comes first. Then compare the results of the two runs – if they differ, there's a bug.

How many orders does it take to reorder every two instructions that could ever run in parallel? (Actually, this requirement is too weak to find all the bugs – we'll plug that hole later – but it's usually enough to find most of the bugs.)

In a fork/join program, you need just two orders:

- run all loops from 0 to N.

- run them all backwards, from N to 0.

Here's an illustration – consider this example pseudo-code with nested parallel loops:

parallel for i=0:2

foo(i)

parallel for j=0:i

bar(i,j)

baz(i)

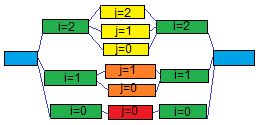

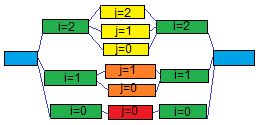

The ordering constraints – which code block can run in parallel with which – make up the following DAG:

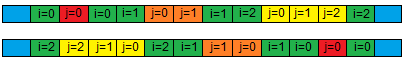

And here are the two schedules – the 0 to N one and the backwards one:

Pick any two instructions that could possibly run in parallel and you'll see that they are reordered in these two schedules.

What happens if you use raw threads and locks?

Then the ordering constraints don't have to look like a simple fork/join DAG. All we can say is that the ordering constraints form some sort of a partial order over the set of serial code blocks (whose instructions are fully ordered).

With N code blocks, an upper bound on the number of orders you might need is N*2. (For every code segment, schedule it to run as early as possible, and then schedule it to run as late as possible – that's N*2 schedules reordering every two independent instructions.)

But N*2 is a lot of orders – N can be rather large. Can we do better, as we did in the fork/join case – by having less schedules which reorder more things?

Perhaps we can – but finding out the lower bound on the number of orders is an NP-hard problem (its standard name is finding the poset dimension). And heuristics analyzing partial orders in an attempt to produce fewer than N*2 orders take minutes to run with N in the few thousands, in my experience.

The upshot is that reordering every pair of independent instructions is trivial with fork/join code and very hard with raw threads.

Now let's consider an improvement upon simple event reordering – memory access monitoring based on something like program instrumentation or a compiler pass.

Plain event reordering has two main drawbacks:

- Some bugs are missed. Consider updates to accumulators. Whether we run sum+=a[5] before or after sum+=a[6], sum will reach the same value – whereas in a parallel run, it may not. (Finer-grained reordering – trying every way to interleave instructions that could run in parallel, and not just reordering every pair of independent instructions – would catch the bug. But that's obviously infeasible.)

- Bugs aren't pinpointed. Reordering gives evidence that you have a bug by demonstrating that results differ under different schedules. But how do you find the bug?

Here's how we can improve upon plain reordering. Let's intercept memory accesses and record the ID of the thread which was the last to write to each and every location – the location's owner. (Logically, each loop index could run in a separate thread – so ideally, we'd map each index to a separate thread ID. In practice, we might want IDs to be small, so we'd use low bits of the index or some such.)

Then if a location is accessed by someone whose ID is different from the owner's ID, we have a bug, and we've pinpointed it – all we need to do is print the current call stack:

checkedthreads: error - thread 56 accessed 0x7FF000340 [0x7FF000340,4], owned by 55 ==2919== at 0x40202C: std::_Function_handler...::_M_invoke (bug.cpp:16) ==2919== by 0x403293: ct_valgrind_for_loop (valgrind_imp.c:62) ==2919== by 0x4031C8: ct_valgrind_for (valgrind_imp.c:82) ==2919== by 0x40283C: ct_for (ct_api.c:177) ==2919== by 0x401E9D: main (bug.cpp:20)

It's a tad more complicated with nested loops but not much more complicated; the details aren't worth discussing here. The point is, this works regardless of whether there's an effect on results that can be reproduced in a serial run. We pinpoint bugs involving accumulators and shared temporary buffers and what-not, even though results look fine in serial runs.

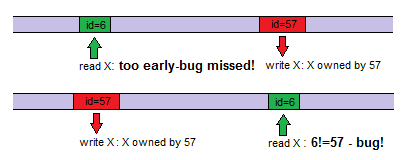

Note that we still rely on event reordering. That's because we catch the bug if an address was written first and then read – but not if it was read first and then written:

This is OK – if you have a reordering scheduler guaranteeing that in one of your runs, the address is actually written first and then read. With such a scheduler and access monitoring, you'll never miss a bug if it could ever happen with your input data – and you'll always have it pinpointed.

Why doesn't it work nearly as well with raw threads and semaphores?

The first problem is, you need a reordering scheduler, and there are too many schedules to cover, as we discussed above. I've shown in the past an example where Helgrind, a memory access monitoring Valgrind tool for debugging pthread applications, misses a bug – because the bug is masked by the order in which things happen to run.

But there's another problem with raw threads and locks, preventing memory access monitoring from pinpointing some of the bugs when they do reproduce.

Specifically, if two threads access a location, and they use a lock to synchronize their accesses, then you can't flag the access as a bug, right? However, it very well may be a bug. It's certainly not a data race (unsynchronized access to memory) – but it can be a race condition (a bug due to event ordering).

As an example, consider a supposedly deterministic simulation (not an interactive game – though the screenshot below is from a game, Lock 'n' Chase). In the simulation, agents run around a maze, picking up coins. Whoever made it first to pick up a coin has won a race – literally!

Suppose each agent is simulated by its own thread. Then it might be that the simulated speed of an agent in the maze depends on the amount of CPU time its thread used compared to others. And then results depend on timing and it's a bug. (A thread per maze region would be a better strategy than a thread per agent.)

This is a race condition – because timing affects results. However, as long as agents lock the coins they pick up, it's not a data race – because access to shared memory is synchronized. And memory access monitoring can only pinpoint data races, not race conditions.

You can simulate a maze, notice that memory where you keep a coin representation is accessed concurrently without locking, and print the offending call stack.

But you can't simulate a maze, notice that with different event ordering, different agents pick up the (properly locked) coin, and "print the offending call stack". There simply is no single offending call stack – only the fact that results end up differing.

John Regehr has a great discussion on the difference between race conditions and data races. Check out his example with a bank account, where all account balances are locked "nicely" – but the bank still doesn't properly transfer money between accounts.

The thing that matters in our context is that with pure fork/join code, all race conditions are data races. In the general case of raw threads, it's no longer true – which gets in the way of pinpointing bugs.

Note that using something like Go's channels or even Erlang's processes doesn't solve the maze race problem – in the sense that you still can't pinpoint bugs. Instead of locking coins, you might have agent processes or goroutines or what-not – and one or several processes keeping coins. Agents would send requests to pick up coins to these processes – and who'd make it first isn't deterministic, and there's no single place in the code "where the bug is".

This is one example of eliminating shared memory and keeping the bugs – as opposed to fork/join code's ability to keep shared memory while (automatically) eliminating the bugs.

(This is not to say that Erlang-style lightweight processes aren't a good idea – they can be great in certain contexts. I do believe that parallelizing computational code is a somewhat different problem from handling concurrent events – and that fork/join parallelism is close to "the right thing" for computational code.)

To summarize the entire discussion of verification:

- With fork/join code, every bug which could possibly manifest with the given inputs can be deterministically reproduced and pinpointed.

- Conversely, with raw threads and locks, it's computationally hard to deterministically reproduce bugs. Furthermore, even reproducible bugs can not always be automatically pinpointed.

It is also notable that with raw threads, you get to worry about deadlocks. With pure fork/join code, there simply can never be a deadlock.

(The analysis above mostly isn't rigorous and you're welcome to correct me.)

Some features of checkedthreads

Noteworthy features of checkedthreads are discussed here. A short summary:

- Guaranteed bug detection as discussed above.

- Integration with other frameworks: if you already use OpenMP or TBB, you can configure checkedthreads to use their scheduler (and their thread pool) instead of fighting over the machine with the other framework.

- Dynamic load balancing: work gets done as soon as a thread is available to do it. Load balancing automatically takes into account variability between the different tasks – as well as whatever unexpected load the CPUs might be handling while running your code.

- A C89 and a C++11 API are available.

- Free as in "do what you want with it" (FreeBSD license).

- Easily portable (in theory).

- Small and simple (at the moment).

- Custom schedulers are very easy to add (though it's more of a recreational activity than a necessity, or so I hope).

Downloading, building, installing and using checkedthreads

I recommend to read the build instructions, and then, possibly, download precompiled binaries. (The build instructions are useful, in particular, to know what you're getting in the binary archive.) The source code of version 1.0 is archived here; [email protected]:yosefk/checkedthreads.git keeps the latest source code.

Before actually using checkedthreads, I recommend to read the rather short documentation of the API, the environment variables, and runtime verification.

If you run into any issues with checkedthreads, drop me a line at [email protected].

Conclusion

To quote the same piece by John Carmack again:

...if you have a large enough codebase, any class of error that is syntactically legal probably exists there.

In other words, "correct by design" is an almost non-existent property; correctness is either demonstrated automatically, or it is absent. While nobody has to make the simple errors we discussed in our toy examples, analogous errors will necessarily creep into large parallel programs.

Checkedthreads shows that for one significant family of parallel imperative programs – fork/join code – it's possible to automatically, deterministically reproduce and pinpoint every bug.

I hope it to be a convincing example of what I think is a more general truth – namely, that parallel imperative programs don't have to be "deeply frightening", any more than serial imperative programs ought to be a scary nest of computed gotos. What we need is the right higher-level interfaces on top of raw threads and locks.

There generally appears to be a necessary trade-off between flexibility and correctness. A lot of widely known approaches to parallelism maximize one at the expense of the other. Raw threads – and many of the higher-level frameworks out there – are very flexible, but it's very hard to know that your code is correct. With pure functional code, you have statically guaranteed determinism – but "no side effects" is a very severe restriction.

Checkedthreads attempts to offer a different balance: determinism guaranteed by testing instead of statically – and an imperative language to program in, albeit with less synchronization options than those available with raw threads.

I hope you like it – and don't hesitate to email me if you need any sort of support :-) (In particular, I'll gladly port the thing to other platforms/languages if people are interested.)