Programmable NVIDIA GPUs are very inspiring to hardware geeks, proving that processors with an original, incompatible programming model can become widely used.

NVIDIA call their parallel programming model SIMT - "Single Instruction, Multiple Threads". Two other different, but related parallel programming models are SIMD - "Single Instruction, Multiple Data", and SMT - "Simultaneous Multithreading". Each model exploits a different source of parallelism:

- In SIMD, elements of short vectors are processed in parallel.

- In SMT, instructions of several threads are run in parallel.

- SIMT is somewhere in between – an interesting hybrid between vector processing and hardware threading.

My presentation of SIMT is focused on hardware architecture and its implications on the trade-off between flexibility and efficiency. I'll describe how SIMT is different from SIMD and SMT, and why – what is gained (and lost) through these differences.

From a hardware design perspective, NVIDIA GPUs are at first glance really strange. The question I'll try to answer is "why would you want to build a processor that way?" I won't attempt to write a GPU programming tutorial, or quantitatively compare GPUs to other processors.

SIMD < SIMT < SMT

It can be said that SIMT is a more flexible SIMD, and SMT is in turn a more flexible SIMT. Less flexible models are generally more efficient – except when their lack of flexibility makes them useless for the task.

So in terms of flexibility, SIMD < SIMT < SMT. In terms of performance, SIMD > SIMT > SMT, but only when the models in question are flexible enough for your workload.

SIMT vs SIMD

SIMT and SIMD both approach parallelism through broadcasting the same instruction to multiple execution units. This way, you replicate the execution units, but they all share the same fetch/decode hardware.

If so, what's the difference between "single instruction, multiple data", and single instruction, multiple threads"? In NVIDIA's model, there are 3 key features that SIMD doesn't have:

- Single instruction, multiple register sets

- Single instruction, multiple addresses

- Single instruction, multiple flow paths

We'll see how this lifts restrictions on the set of programs that are possible to parallelize, and at what cost.

Single instruction, multiple register sets

Suppose you want to add two vectors of numbers. There are many ways to spell this. C uses a loop spelling:

for(i=0;i<n;++i) a[i]=b[i]+c[i];

Matlab uses a vector spelling:

a=b+c;

SIMD uses a "short vector" spelling – the worst of both worlds. You break your data into short vectors, and your loop processes them using instructions with ugly names. An example using C intrinsic functions mapping to ARM NEON SIMD instructions:

void add(uint32_t *a, uint32_t *b, uint32_t *c, int n) {

for(int i=0; i<n; i+=4) {

//compute c[i], c[i+1], c[i+2], c[i+3]

uint32x4_t a4 = vld1q_u32(a+i);

uint32x4_t b4 = vld1q_u32(b+i);

uint32x4_t c4 = vaddq_u32(a4,b4);

vst1q_u32(c+i,c4);

}

}

SIMT uses a "scalar" spelling:

__global__ void add(float *a, float *b, float *c) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

a[i]=b[i]+c[i]; //no loop!

}

The weird __global__ keyword says that add() is a GPU thread entry point. blockIdx, blockDim and threadIdx are built-in thread-local variables keeping the thread's ID. We'll see later why a thread ID isn't just a single number; however, in this example we in fact convert it to a single number, and use it as the element index.

The idea is that the CPU spawns a thread per element, and the GPU then executes those threads. Not all of the thousands or millions of threads actually run in parallel, but many do. Specifically, an NVIDIA GPU contains several largely independent processors called "Streaming Multiprocessors" (SMs), each SM hosts several "cores", and each "core" runs a thread. For instance, Fermi has up to 16 SMs with 32 cores per SM – so up to 512 threads can run in parallel.

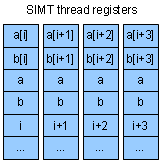

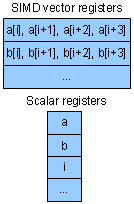

All threads running on the cores of an SM at a given cycle are executing the same instruction – hence Single Instruction, Multiple Threads. However, each thread has its own registers, so these instructions process different data.

Benefits

"Scalar spelling", where you write the code of a single thread using standard arithmetic operators, is arguably a better interface than SIMD loops with ugly assembly-like opcodes.

Syntax considerations aside, is this spelling more expressive – can it do things SIMD can't? Not by itself, but it dovetails nicely with other features that do make SIMT more expressive. We'll discuss those features shortly; in theory, they could be bolted on the SIMD model, but they never are.

Costs

From a hardware resources perspective, there are two costs to the SIMT way:

- Registers spent to keep redundant data items.

In our example,

the pointers a, b, and c have the same value in all threads. The values of i are different across threads, but in a trivial way

– for instance, 128, 129, 130... In SIMD, a, b, and c would be kept once in “scalar” registers – only short vectors such as

a[i:i+4] would be kept in “vector” registers. The index i would also be kept once – several neighbor elements starting from i

would be accessed without actually computing i+1, i+2, etc. Redundant computations both waste registers and needlessly consume

power. Note, however, that a combination of compiler & hardware optimizations could eliminate the physical replication of

redundant values. I don't know the extent to which it's done in reality.

In our example,

the pointers a, b, and c have the same value in all threads. The values of i are different across threads, but in a trivial way

– for instance, 128, 129, 130... In SIMD, a, b, and c would be kept once in “scalar” registers – only short vectors such as

a[i:i+4] would be kept in “vector” registers. The index i would also be kept once – several neighbor elements starting from i

would be accessed without actually computing i+1, i+2, etc. Redundant computations both waste registers and needlessly consume

power. Note, however, that a combination of compiler & hardware optimizations could eliminate the physical replication of

redundant values. I don't know the extent to which it's done in reality. - Narrow data types are as costly as wide data types.

A SIMD vector

register keeping 4 32b integers can typically also be used to keep 8 16b integers, or 16 8b ones. Similarly, the same ALU

hardware can be used for many narrow additions or fewer wide ones – so 16 byte pairs can be added in one cycle, or 4 32b integer

pairs. In SIMT, a thread adds two items at a time, no matter what their width, wasting register bits and ALU circuitry.

A SIMD vector

register keeping 4 32b integers can typically also be used to keep 8 16b integers, or 16 8b ones. Similarly, the same ALU

hardware can be used for many narrow additions or fewer wide ones – so 16 byte pairs can be added in one cycle, or 4 32b integer

pairs. In SIMT, a thread adds two items at a time, no matter what their width, wasting register bits and ALU circuitry.

It should be noted that SIMT can be easily amended with SIMD extensions for narrow types, so that each thread processes 4 bytes at a time using ugly assembly-like opcodes. AFAIK, NVIDIA refrains from this, presumably assuming that the ugliness is not worth the gain, with 32b float being the most popular data type in graphics anyway.

Single instruction, multiple addresses

Let's apply a function approximated by a look-up table to the elements of a vector:

__global__ void apply(short* a, short* b, short* lut) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

a[i] = lut[b[i]]; //indirect memory access

}

Here, i is again "redundant" in the sense that in parallel threads, the values of i are consecutive. However, each thread then accesses the address lut+b[i] – and these addresses are not consecutive.

Roughly, such parallel random access works for both loads and stores. Logically, stores are the trickier part because of conflicts. What if two or more threads attempt to, say, increment the same bin in a histogram? Different NVIDIA GPU generations provide different solutions that we won't dwell on.

Benefits

This feature lets you parallelize many programs you can't with SIMD. Some form of parallel random access is usually available on SIMD machines under the names "permutation", "shuffling", "table look-up", etc. However, it always works with registers, not with memory, so it's just not the same scale. You index into a table of 8, 16 or 32 elements, but not 16K.

As previously mentioned, in theory this feature can be bolted on the SIMD model: just compute your addresses (say, lut+b[i]) in vector registers, and add a rand_vec_load instruction. However, such an instruction would have a fairly high latency. As we'll see, the SIMT model naturally absorbs high latencies without hurting throughput; SIMD much less so.

Costs

GPU has many kinds of memory: external DRAM, L2 cache, texture memory, constant memory, shared memory... We'll discuss the cost of random access in the context of two memories "at the extremes": DRAM and shared memory. DRAM is the farthest from the GPU cores, sitting outside the chip. Shared memory is the closest to the cores – it's local to an SM, and the cores of an SM can use it to share results with each other, or for their own temporary data.

- With DRAM memory, random access is never efficient. In fact, the GPU hardware looks at all memory addresses that the running threads want to access at a given cycle, and attempts to coalesce them into a single DRAM access – in case they are not random. Effectively the contiguous range from i to i+#threads is reverse-engineered from the explicitly computed i,i+1,i+2... – another cost of replicating the index in the first place. If the indexes are in fact random and can not be coalesced, the performance loss depends on "the degree of randomness". This loss results from the DRAM architecture quite directly, the GPU being unable to do much about it – similarly to any other processor.

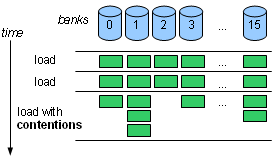

- With shared memory, random access is slowed down by bank contentions. Generally, a hardware memory module will only service one access at a time. So shared memory is organized in independent banks; the number of banks for NVIDIA GPUs is 16. If x is a variable in shared memory, then it resides in bank number (&x/4)%16. In other words, if you traverse an array, the bank you hit changes every 4 bytes. Access throughput peaks if all addresses are in different banks – hardware contention detection logic always costs latency, but only actual contentions cost throughput. If there's a bank hosting 2 of the addresses, the throughput is 1/2 of the peak; if there's a bank pointed by 3 addresses, the throughput is 1/3 of the peak, etc., the worst slowdown being 1/16.

In theory, different mappings between banks and addresses are possible, each with its own shortcomings. For instance, with NVIDIA's mapping, accessing a contiguous array of floats gives peak throughput, but a contiguous array of bytes gives 1/4 of the throughput (since banks change every 4 bytes). Many of the GPU programming tricks aim at avoiding contentions.

For instance, with a byte array, you can frequently work with bytes at distance 4 from each other at every given step. Instead of accessing a[i] in your code, you access a[i*4], a[i*4+1], a[i*4+2] and a[i*4+3] – more code, but less contentions.

This sounds convoluted, but it's a relatively cheap way for the hardware to provide efficient random access. It also supports some very complicated access patterns with good average efficiency – by handling the frequent case of few contentions quickly, and the infrequent case of many contentions correctly.

Single instruction, multiple flow paths

Let's find the indexes of non-zero elements in a vector. This time, each thread will work on several elements instead of just one:

__global__ void find(int* vec, int len,

int* ind, int* nfound,

int nthreads) {

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int last = 0;

int* myind = ind + tid*len;

for(int i=tid; i<len; i+=nthreads) {

if(vec[i]) { //flow divergence

myind[last] = i;

last++;

}

}

nfound[tid] = last;

}

Each thread processes len/nthreads elements, starting at the index equal to its ID with a step of nthreads. We could make each thread responsible for a more natural contiguous range using a step of 1. The way we did it is better in that accesses to vec[i] by concurrent threads address neighbor elements, so we get coalescing.

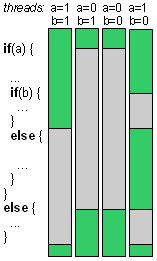

The interesting bit is if(vec[i]) – depending on vec[i], some threads execute the code saving the index, some don't. The control flow of different threads can thus diverge.

Benefits

Support for divergence further expands the set of parallelizable programs, especially when used together with parallel random access. SIMD has some support for conditional execution though vector "select" operations: select(flag,a,b) = if flag then a else b. However, select can't be used to suppress updates to values – the way myind[last] is never written by threads where vec[i] is 0.

SIMD instructions such as stores could be extended to suppress updates based on a boolean vector register. For this to be really useful, the machine probably also needs parallel random access (for instance, the find() example wouldn't work otherwise). Unless what seems like an unrealistically smart compiler arrives, this also gets more and more ugly, whereas the SIMT spelling remains clean and natural.

Costs

- Only one flow path is executed at a time, and threads not running it must wait.

Ultimately SIMT executes a single instruction in all the multiple threads it runs

– threads share program memory and fetch / decode / execute logic. When the threads have the same flow – all run the

if, nobody runs the else, for example – then they just all run the code in if at full throughput.

However, when one or more threads have to run the else, they'll wait for the if threads. When the if

threads are done, they'll in turn wait for the else threads. Divergence is handled correctly, but slowly. Deeply nested

control structures effectively serialize execution and are not recommended.

Ultimately SIMT executes a single instruction in all the multiple threads it runs

– threads share program memory and fetch / decode / execute logic. When the threads have the same flow – all run the

if, nobody runs the else, for example – then they just all run the code in if at full throughput.

However, when one or more threads have to run the else, they'll wait for the if threads. When the if

threads are done, they'll in turn wait for the else threads. Divergence is handled correctly, but slowly. Deeply nested

control structures effectively serialize execution and are not recommended. - Divergence can further slow things down through "randomizing" memory access. In our example, all threads read vec[i], and the indexing is tweaked to avoid contentions. However, when myind[last] is written, different threads will have incremented the last counter a different number of times, depending on the flow. This might lead to contentions which also serialize execution to some extent. Whether the whole parallelization exercise is worth the trouble depends on the flow of the algorithm as well as the input data.

We've seen the differences between SIMT and its less flexible relative, SIMD. We'll now compare SIMT to SMT – the other related model, this time the more flexible one.

SIMT vs SMT

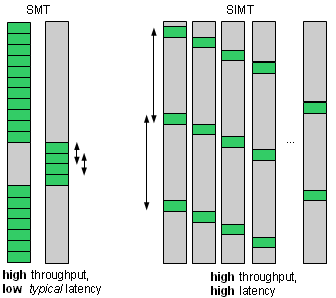

SIMT and SMT both use threads as a way to improve throughput despite high latencies. The problem they tackle is that any single thread can get stalled running a high-latency instruction. This leaves the processor with idle execution hardware.

One way around this is switching to another thread – which (hopefully) has an instruction ready to be executed – and then switch back. For this to work, context switching has to be instantaneous. To achieve that, you replicate register files so that each thread has its own registers, and they all share the same execution hardware.

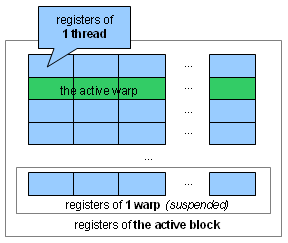

But wait, doesn't SIMT already replicate registers, as a way to have a single instruction operate on different data items? It does – here, we're talking about a "second dimension" of register replication:

- Several threads – a "warp" in NVIDIA terminology – run simultaneously. So each thread needs its own registers.

- Several warps, making up a "block", are mapped to an SM, and an SM instantaneously switches between the warps of a block. So each warp needs separate registers for each of its threads.

With this "two-dimensional" replication, how many registers we end up with? Well, a lot. A block can have up to 512 threads. And the registers of those threads can keep up to 16K of data.

How many register sets does a typical SMT processor have? Er, 2, sometimes 4...

Why so few? One reason is diminishing returns. When you replicate registers, you pay a significant price, in the hope of being able to better occupy your execution hardware. However, with every thread you add, the chance of it being already occupied by all the other threads rises. Soon, the small throughput gain just isn't worth the price.

If SMT CPU designers stop at 2 or 4 threads, why did SIMT GPU designers go for 512?

With enough threads, high throughput is easy

SMT is an afterthought – an attempt to use idle time on a machine originally designed to not have a lot of idle time to begin with. The basic CPU design aims, first and foremost, to run a single thread fast. Splitting a process to several independent threads is not always possible. When it is possible, it's usually gnarly.

Even in server workloads, where there's naturally a lot of independent processing, single-threaded latency still matters. So few expensive, low-latency cores outperform many cheap, high-latency cores. As Google's Urs Hölzle put it, "brawny cores beat wimpy cores". Serial code has to run fast.

Running a single thread fast means being able to issue instructions from the current thread as often as possible. To do that, CPU hardware works around every one of the many reasons to wait. Such diverse techniques as:

- superscalar execution

- out-of-order execution

- register renaming

- branch prediction

- speculative execution

- cache hierarchy

- speculative prefetching

- etc. etc.

...are all there for the same basic purpose. They maximize the chances of an instruction to be issued without having to switch to another thread.

SMT is the last line of defense, attempting to fill stalls after all these other measures failed. And even that is considered a bad idea when it hurts the precious single-threaded performance. Which it usually does: each of the 2 threads will typically complete later then it would if it didn't have to share the hardware with the other. This is a key reason to keep the number of hardware threads low, even if there are still throughput gains to be made by adding threads.

However, for the GPUs, the use case is when you do have enough data parallelism to make use of plenty of threads. If so, why not build things the other way around? Threading could be our first stall-mitigating measure. If we have enough threads, we just keep switching between them, and the hardware always has something to do.

This saves a lot of hardware, and a lot of design effort, because you don't need most of the other methods anymore. Even caches and hardware prefetching are not used in much of the GPU memory traffic – rather, you access external memory directly. Why bother with caching and prefetching, if you don't have to sit idly until the data arrives from main memory – but instead just switch to a different warp? No heuristics, no speculation, no hurry – just keep yourself busy when waiting.

Furthermore, even the basic arithmetic pipeline is designed for a high latency, high throughput scenario. According to the paper "Demystifying GPU architecture through microbenchmarking", no operation takes less than 24 cycles to complete. However, the throughput of many operations is single-cycle.

The upshot is that counting on the availability of many threads allows the GPU to sustain a high throughput without having to sweat for low latencies. Hardware becomes simpler and cheaper in many areas as a result.

When latencies are high, registers are cheap

So plentiful threads make it easier to build high-throughput hardware. What about having to replicate all those registers though? 16K sounds like an insane amount of registers – how is this even affordable?

Well, it depends on what "register" means. The original meaning is the kind of storage with the smallest access latency. In CPUs, access to registers is faster than access to L1 caches, which in turn is faster than L2, etc. Small access latency means an expensive implementation, therefore there must be few registers.

However, in GPUs, access to "registers" can be quite slow. Because the GPU is always switching between warps, many cycles pass between two subsequent instructions of one warp. The reason registers must be fast in CPUs is because subsequent instructions communicate through them. In GPUs, they also communicate through registers – but the higher latency means there's no rush.

Therefore, GPU registers are only analogous to CPU registers in terms of instruction encoding. In machine code, "registers" are a small set of temporary variables that can be referenced with just a few bits of encoding – unlike memory, where you need a longer address to refer to a variable. In this and other ways, "registers" and "memory" are semantically different elements of encoding – both on CPUs and GPUs.

However, in terms of hardware implementation, GPU registers are actually more like memory than CPU registers. [Disclaimer: NVIDIA doesn't disclose implementation details, and I'm grossly oversimplifying, ignoring things like data forwarding, multiple access ports, and synthesizable vs custom design]. 16K of local RAM is a perfectly affordable amount. So while in a CPU, registers have to be expensive, they can be cheap in a high-latency, high-throughput design.

It's still a waste if 512 threads keep the same values in some of their registers – such as array base pointers in our examples above. However, many of the registers keep different values in different threads. In many cases register replication is not a waste at all – any processor would have to keep those values somewhere. So functionally, the plentiful GPU registers can be seen as a sort of a data cache.

Drawbacks

We've seen that:

- Many threads enable cheap high-throughput, high-latency design

- A high-throughput, high-latency design in turn enables a cheap implementation of threads' registers

This leads to a surprising conclusion that SIMT with its massive threading can actually be cheaper than SMT-style threading added to a classic CPU design. Not unexpectedly, these cost savings come at a price of reduced flexibility:

- Low occupancy greatly reduces performance

- Flow divergence greatly reduces performance

- Synchronization options are very limited

Occupancy

"Occupancy" is NVIDIA's term for the utilization of threading. The more threads an SM runs, the higher its occupancy. Low occupancy obviously leads to low performance – without enough warps to switch between, the GPU won't be able to hide its high latencies. The whole point of massive threading is refusing to target anything but massively parallel workloads. SMT requires much less parallelism to be efficient.

Divergence

We've seen that flow divergence is handled correctly, but inefficiently in SIMT. SMT doesn't have this problem – it works quite well given unrelated threads with unrelated control flow.

There are two reasons why unrelated threads can't work well with SIMT:

- SIMD-style instruction broadcasting – unrelated threads within a warp can't run fast.

- More massive threading than SMT – unrelated wraps would compete for shared resources such as instruction cache space. SMT also has this problem, but it's tolerable when you have few threads.

So both of SIMT's key ideas – SIMD-style instruction broadcasting and SMT-style massive threading – are incompatible with unrelated threads.

Related threads – those sharing code and some of the data – could work well with massive threading by itself despite divergence. It's instruction broadcasting that they fail to utilize, leaving execution hardware in idle state.

However, it seems that much of the time, related threads actually tend to have the same flow and no divergence. If this is true, a machine with massive threading but without instruction broadcasting would miss a lot of opportunities to execute its workload more efficiently.

Synchronization

In terms of programming model, SMT is an extension to a single-threaded, time-shared CPU. The same fairly rich set of inter-thread (and inter-device) synchronization and communication options is available with SMT as with "classic" single-threaded CPUs. This includes interrupts, message queues, events, semaphores, blocking and non-blocking system calls, etc. The underlying assumptions are:

- There are quite many threads

- Typically, each thread is doing something quite different from other threads

- At any moment, most threads are waiting for an event, and a small subset can actually run

SMT stays within this basic time-sharing framework, adding an option to have more than one actually running threads. With SMT, as with a "classic" CPU, a thread will be very typically put "on hold" in order to wait for an event. This is implemented using context switching – saving registers to memory and, if a ready thread is found, restoring its registers from memory so that it can run.

SIMT doesn't like to put threads on hold, for several reasons:

- Typically, there are many running, related threads. It would make the most sense to put them all on hold, so that another, unrelated, equally large group of threads can run. However, switching 16K of context is not affordable. In this sense, "registers" are expensive after all, even if they are actually memory.

- SIMT performance depends greatly on there being many running threads. There's no point in supporting the case where most threads are waiting, because SIMT wouldn't run such workloads very well anyway. From the use case angle, a lot of waiting threads arise in "system"/"controller" kind of software, where threads wait for files, sockets, etc. SIMT is purely computational hardware that doesn't support such OS services. So the situation is both awkward for SIMT and shouldn't happen in its target workloads anyway.

- Roughly, SIMT supports data parallelism – same code, different data. Data parallelism usually doesn't need complicated synchronization – all threads have to synchronize once a processing stage is done, and otherwise, they're independent. What requires complicated synchronization, where some threads run and some are put on hold due to data dependencies, is task parallelism – different code, different data. However, task parallelism implies divergence, and SIMT isn't good at that anyway – so why bother with complicated synchronization?

Therefore, SIMT roughly supports just one synchronization primitive – __syncthreads(). This creates a synchronization point for all the threads of a block. You know that if a thread runs code past this point, no thread runs code before this point. This way, threads can safely share results with each other. For instance, with matrix multiplication:

- Each thread, based on its ID – x,y – reads 2 elements, A(x,y) and B(x,y), from external memory to the on-chip shared memory. (Of course large A and B won't fit into shared memory, so this will be done block-wise.)

- Threads sync – all threads can now safely access all of A and B.

- Each thread, depending on the ID, multiplies row y in A by column x in B.

//1. load A(x,y) and B(x,y) int x = threadIdx.x; int y = threadIdx.y; A[stride*y + x] = extA[ext_stride*y + x]; B[stride*y + x] = extB[ext_stride*y + x]; //2. sync __syncthreads(); //3. multiply row y in A by column x in B float prod = 0; for(int i=0; i<N; ++i) { prod += A[stride*y + i] * B[stride*i + x]; }

It's an incomplete example (we look at just one block and ignore blockIdx, among other thing), but it shows the point of syncing – and the point of these weird "multi-dimensional" thread IDs (IDs are x,y,z coordinates rather than just integers). It's just natural, with 2D and 3D arrays, to map threads and blocks to coordinates and sub-ranges of these arrays.

Summary of differences between SIMD, SIMT and SMT

SIMT is more flexible in SIMD in three areas:

- Single instruction, multiple register sets

- Single instruction, multiple addresses

- Single instruction, multiple flow paths

SIMT is less flexible than SMT in three areas:

- Low occupancy greatly reduces performance

- Flow divergence greatly reduces performance

- Synchronization options are very limited

The effect of flexibility on costs was discussed above. A wise programmer probably doesn't care about these costs – rather, he uses the most flexible (and easily accessible) device until he runs out of cycles, then moves on to utilize the next most flexible device. Costs are just a limit on how flexible a device that is available in a given situation can be.

"SIMT" should catch on

It's a beautiful idea, questioning many of the usual assumptions about hardware design, and arriving at an internally consistent answer with the different parts naturally complementing each other.

I don't know the history well enough to tell which parts are innovations by NVIDIA and which are borrowed from previous designs. However, I believe the term SIMT was coined by NVIDIA, and perhaps it's a shame that it (apparently) didn't catch, because the architecture "deserves a name" – not necessarily true of every "new paradigm" announced by marketing.

One person who took note is Andy Glew, one of Intel's P6 architects – in his awesome computer architecture wiki, as well as in his presentation regarding further development of the SIMT model.

The presentation talks about neat optimizations – "rejiggering threads", per-thread loop buffers/time pipelining – and generally praises SIMT superiority over SIMD. Some things I disagree with – such as the "vector lane crossing" issue – and some are very interesting, such as everything about improving utilization of divergent threads.

I think the presentation should be understandable after reading my oversimplified overview – and will show where my overview oversimplifies, among other things.

Peddling fairness

Throughout this overview, there's this recurring "fairness" idea: you can trade flexibility for performance, and you can choose your trade-off.

It makes for a good narrative, but I don't necessarily believe it. You might very well be able to get both flexibility and performance. More generally, you might get both A and B, where A vs B intuitively feels like "an inherent trade-off".

What you can't do is get A and B in a reasonably simple, straightforward way. This means that you can trade simplicity for almost everything – though you don't necessarily want to; perhaps it's a good subject for a separate post.